Monday, February 27, 2012

Sunday, February 26, 2012

bullhorns.

I'M GOING TO SEE JON STEWART ON TOUR DOWN HERE IN APRIL! Saw Colbert live in NYC back in '07, so it's only customary to see my other gentlesir I love so very, very dearly. All is perhaps too well in Karynland at the moment... might have to slap oneself back into 'reality', whatever that may be.

Other funny thing: all the random people on the bus that inquire about the book I've been reading by Matt Taibbi... the fancy cover with the White House hooks 'em into asking, even though they nonchalantly admit to me their conservative leanings. One guy was like "I'm going to order that when I get home!" to which I say, you do that, ... guy.

Day by day all the bullshit thats happening is fueling the fire in my fingertips to lash against the idiocracy. Latest being, you're going to deny my little Sue (60 yr old lady at work, biggest sweetheart in the world) an MRI for her fucked up back because shes uninsured but has been a lifelong law abiding American citizen and a hardworking tax paying one since she was 15? Oh no no no. Your time is nearly up for getting away with this hogwash. I have had it up to here, asshat inside groups... while my pain is nearly over, seeing little sues pain hurts all of us so much, my co-worker kara and I were fighting tears the other day. you just don't fuck with little sue. or you'll get the ...

Other funny thing: all the random people on the bus that inquire about the book I've been reading by Matt Taibbi... the fancy cover with the White House hooks 'em into asking, even though they nonchalantly admit to me their conservative leanings. One guy was like "I'm going to order that when I get home!" to which I say, you do that, ... guy.

Day by day all the bullshit thats happening is fueling the fire in my fingertips to lash against the idiocracy. Latest being, you're going to deny my little Sue (60 yr old lady at work, biggest sweetheart in the world) an MRI for her fucked up back because shes uninsured but has been a lifelong law abiding American citizen and a hardworking tax paying one since she was 15? Oh no no no. Your time is nearly up for getting away with this hogwash. I have had it up to here, asshat inside groups... while my pain is nearly over, seeing little sues pain hurts all of us so much, my co-worker kara and I were fighting tears the other day. you just don't fuck with little sue. or you'll get the ...

Thursday, February 23, 2012

pure escapist bullshit

Haven't begun writing anything yet... the books I ordered came in the mail yesterday; started reading Matt Taibbi's The Great Derangement (and have Griftopia to read afterwards) which I believe will help give me ideas in regards to what my character already knows about the failed system. In honor of the great Gonzo journalists, I'm stepping out of my body and into my mind today (on a day off, in my apartment, no worries...) Ready for some exciting inspiration to fwap me in the ol' skullular arena. (my brain is a colosseum and inside is a vicious square off between the arrogant ox and scarface, the two elements that have kept me from writing. hopefully they will beat each other to a bloody pulp, for nothing can happen until both have been banished!)

Tuesday, February 21, 2012

Blahdeeblahblah

Gee, coming home and smelling like a saucy senior really tickles my fancy... every snowbird that stepped onto the bus today presumably had dumped a bucketload of Liz Claiborne over their head... or bathed in it.

Unfortunately I'm so exhausted.... what I really need to do is start the first page of my novel I have finally situated the background/settings/premise for... even asked some closer co-workers today if I could take their e-mail addresses to send them parts for critique, of course there's always my fellow writer mister luvaluva --- but he might be too harsh. ;) It would be SO much better if I had traveling involved to gather material (character is making their way to Washington with a list of major problems and solutions to bring to our fearless leader, figured a giant scroll being unrolled would make for a good visual, even as it tumbles down the stairs inside the White House and goes right out the front door, cascading down to the monuments and so forth) but I'll do my own research and questioning (asking others a melange of questions, ie: one major thing they'd like to see change, the one thing that would help them the most, what worries them to death, wishes, hopes, dreams...) the character has this mixture of Hermes and Paul Revere about them, wanting to be the messenger of the people who believe their voices have never been heard. Little do they also know the dark side of the character, who wants to get to the bottom of this, no matter what it takes. (I've constantly humored myself with 'plans' to secretly infiltrate the high places of power in this country that are so corrupt, their doors are sealed tight, and their PR shmucks who sadly call themselves journalists write trash to keep them all in positive light. Here's to wishing those shmucks would evolve into muckrakers.) I figure since it's not realistic or ever feasible to actually get into that Oval Office, and turn around slowly in that giant armchair to confront the President, a crazy fictious tale should be written, so I can stop these silly fantasies and maybe get heard by writing a testament for the people, by the people.

With that said, I'm going to push myself to start..... after a nap... and after being a little bummed I can't visit up North till May, when the snowbirds finally leave. Siiiighhhhh....

Unfortunately I'm so exhausted.... what I really need to do is start the first page of my novel I have finally situated the background/settings/premise for... even asked some closer co-workers today if I could take their e-mail addresses to send them parts for critique, of course there's always my fellow writer mister luvaluva --- but he might be too harsh. ;) It would be SO much better if I had traveling involved to gather material (character is making their way to Washington with a list of major problems and solutions to bring to our fearless leader, figured a giant scroll being unrolled would make for a good visual, even as it tumbles down the stairs inside the White House and goes right out the front door, cascading down to the monuments and so forth) but I'll do my own research and questioning (asking others a melange of questions, ie: one major thing they'd like to see change, the one thing that would help them the most, what worries them to death, wishes, hopes, dreams...) the character has this mixture of Hermes and Paul Revere about them, wanting to be the messenger of the people who believe their voices have never been heard. Little do they also know the dark side of the character, who wants to get to the bottom of this, no matter what it takes. (I've constantly humored myself with 'plans' to secretly infiltrate the high places of power in this country that are so corrupt, their doors are sealed tight, and their PR shmucks who sadly call themselves journalists write trash to keep them all in positive light. Here's to wishing those shmucks would evolve into muckrakers.) I figure since it's not realistic or ever feasible to actually get into that Oval Office, and turn around slowly in that giant armchair to confront the President, a crazy fictious tale should be written, so I can stop these silly fantasies and maybe get heard by writing a testament for the people, by the people.

With that said, I'm going to push myself to start..... after a nap... and after being a little bummed I can't visit up North till May, when the snowbirds finally leave. Siiiighhhhh....

Sunday, February 19, 2012

I can feel the internet cringing.

The many randomized efforts of creativity, online:

Links to my:

Tumblr (new!)

Feel free to browse. I feel no remorse. (For these, at least.)

Saturday, February 18, 2012

Charlie Chaplin - The Kid

got so involved in this movie, was getting wispy eyed when they kept getting split up... but also loved the parts where the light post was bent over by a mere 'lick' and when his blanket doubled as a poncho.

if I ever got the chance to start in a movie, I would want it to be a silent one with an orchestra/band playing the score.

Friday, February 17, 2012

Wednesday, February 15, 2012

Monday, February 13, 2012

Shut up Economists, we're not idiots, we know whose side you're on.

Why Wall Street Should Stop Whining by Matt Taibbi

Everybody on Wall Street is talking about the new piece by New York magazine’s Gabriel Sherman, entitled "The End of Wall Street as They Knew It."

The article argues that Barack Obama killed everything that was joyful about the banking industry through his suffocating Dodd-Frank reform bill, which forced banks to strip themselves of "the pistons that powered their profits: leverage and proprietary trading."

Having to say goodbye to excess borrowing and casino gambling, the argument goes, has cut into banking profits, leading to extreme decisions like Morgan Stanley’s recent dictum capping cash bonuses at $125,000. In response to that, Sherman quotes an unnamed banker:

"After tax, that’s like, what, $75,000?" an investment banker at a rival firm said as he contemplated Morgan Stanley’s decision. He ran the numbers, modeling the implications. "I’m not married and I take the subway and I watch what I spend very carefully. But my girlfriend likes to eat good food. It all adds up really quick. A taxi here, another taxi there. I just bought an apartment, so now I have a big old mortgage bill."Quelle horreur! And who’s to blame? According to Sherman's interview subjects, it has nothing to do with the economy having been blown up several times over by these very bonus-deprived bankers, or with the fact that all conceivable public bailout money has essentially already been sucked up and converted into bonuses by that same crowd.

No, it instead apparently has everything to do with the Dodd-Frank bill, and specifically the Volcker rule banning proprietary trading, which incidentally hasn’t gone into effect yet.

He quotes Dick Bove, the noted analyst who last year downgraded Goldman Sachs. Bove’s quote on the bonus sadness:

"The government has strangled the financial system," banking analyst Dick Bove told me recently. "We’ve basically castrated these companies. They can’t borrow as much as they used to borrow."When I read things like this I’m simultaneously amazed by two things. The first is the unbelievable tone-deafness of people who would complain out loud, during a time when millions of people around the country are literally losing their homes, that their bonuses – not their total compensation, mind you, but just their cash bonuses, paid in addition to their salaries and their stock packages – are barely enough to cover the mortgage payments for their new condos, the taxis they take when walking is too burdensome, and their girlfriends with expensive tastes.

The second thing that amazes me is that Sherman is buying all this. I don’t know this reporter at all, and I’m happy to concede that he probably hangs out with more Wall Street people than I do. But I’m still in touch with plenty of people in the business, and I have yet to have any investment bankers crying on my shoulder about how the Dodd-Frank bill is forcing them into generic breakfast cereals.

Now, I’m sure if you put it to them the right way – "Hey, Mr. Habitually Overpaid Banker, do you think Barack Obama and the Dodd-Frank bill are ruining your bonus season?" – you’ll get a good percentage of people who’ll take that cheese and cough out the desired quote.

But in reality? Please. Wall Street people complain a lot, but in the last six months, the grave impact of Dodd-Frank on bonuses hasn’t even been within ten miles of the things these people are really panicked about. The comments I’ve heard have been more like, "My asshole has been puckered completely shut for four months in a row over this Europe business," or, "If the ECB doesn’t come up with a Greek bailout package, I’m going to have to sell my children for dog food."

Bonuses are indeed down this year, especially when compared with the bonuses of recent years, but let’s be clear about why. It has nothing to do with Dodd-Frank. We can posit three other factors:

1. Banks have unfortunately had to give up the practice of simply printing trillions of dollars out of thin air by selling off worthless mortgages for huge profits and/or making millions of synthetic copies of those same worthless mortgage assets;

2. After twice being saved from the execution chamber by Ben Bernanke’s Quantitative Easing programs, which printed trillions of new dollars and injected them straight into Wall Street’s arm, Wall Street was rocked this summer when Helicopter Ben decided to temporarily forestall QE3;

3. Europe, a slightly more than minor factor in the global financial picture, is imploding, causing mass hoarding of assets all over the world, severely impacting the business of investment banks everywhere.

Now, Sherman barely even mentions Europe in his article, which is interesting, because the banks on whose behalf he wails so loudly in this piece have mostly all pointed to Europe as more or less the sole reason for their reduced revenues of late.

Take for instance Lloyd Blankfein and Goldman, Sachs. Lloyd has the most famous reduced bonus on Wall Street – he’s making $7 million this year (it was $12.6 million last year) as his bank, Goldman, had a disastrous fourth quarter. Goldman’s $6.1 billion in revenues was down 30% off last year’s fourth quarter. To what does the big Lloyd attribute this sad development?

"This past year was dominated by global macro-economic concerns which significantly affected our clients' risk tolerance and willingness to transact," Blankfein said, "While our results declined as a consequence, I am pleased that the firm retained its industry-leading positions across our global client franchise while prudently managing risk, capital and expenses. As economies and markets improve – and we see encouraging signs of this – Goldman Sachs is very well positioned to perform for our clients and our shareholders."Translation: Europe is such a mess right now that all our biggest clients are sitting on their money instead of letting us steal it from them. However, once Europe rebounds, as we expect it to, we will be well positioned to start stealing from them again.

Goldman’s numbers offer a hilarious counterpoint to Sherman’s piece. The bank’s earnings in total for last year were $4.4 billion, down some 65% off of last year’s numbers. Its revenues for the year were down 26%. Despite these bummerific numbers, Goldman reduced bonuses and compensation by only 21%, down to (a mere) $12.2 billion. If the era of outsized bonuses is over, how come the biggest banks aren’t even cutting them to match revenues, much less profits? One could even interpret Goldman’s numbers as a major increase in the size of the bonus pool, relative to earnings.

But what about other banks? Well, Citigroup also saw a drop in revenues for the year (although its net income actually went up, from $10.6 billion to $11.3 billion). But what was most concerning was the bank’s crappy fourth quarter, when it suffered an 11% drop in earnings.

So where did CEO Vikram Pandit lay the blame for the lost revenue? Dodd-Frank? Reduced leverage? Uh, no. He blamed Europe, too:

"Clearly, the macro environment has impacted the capital markets and we will continue to right-size our businesses to match the environment," Pandit said.How about JP Morgan Chase? The bank’s CEO, Jamie Dimon, was breathlessly quoted in the Sherman piece, and in fact had this to say to Sherman about the culture change:

"Certain products are gone forever," Dimon tells Sherman. "Fancy derivatives are mostly gone. Prop trading is gone. There’s less leverage everywhere."So it’s prop trading and derivatives that’s the problem? That’s not what Wall Street analysts said, when Chase posted a 23% drop in earnings in the fourth quarter. While Dimon in a Q&A last month did go off on the potential problems the Volcker rule might inspire in the future, he was careful to note that those problems are still very much future problems ("I'm going to put Volcker aside, okay, because that really hasn't been written yet").

Instead, virtually every headline about Chase's fourth-quarter earnings drop pegged Euro troubles. "JPMorgan Chase (JPM) ended a long run of profit gains when it logged a steep drop in fourth-quarter earnings Friday, as weakness in Europe contributed to a decline in investment banking revenue," wrote Investor’s Business Daily.

The Telegraph commented thusly: "JPMorgan Chase chief executive Jamie Dimon struck a positive note on the outlook for the US economy even as Europe's debt crisis dragged down the bank's quarterly profits."

And Dimon himself seemed to go along with his counterparts at Goldman and Citi in blaming macro troubles for the recent drop, talking about issues with the "current environment":

The bank's third-quarter profit fell 4% as its businesses were hit hard by Europe's financial woes and the fragile recovery in the United States...When I look at the revenue and bonus numbers on Wall Street this year, I see a number of companies that, despite being functionally insolvent in reality and dependent upon a combination of corrupt accounting and cheap cash from the Fed to survive, are still paying out enormous amounts of money in compensation.

"All things considered, we believe the firm's returns were reasonable given the current environment," said Jamie Dimon, JP Morgan's chairman and chief executive.

In fact, when one considers the lost billions and trillions from the end of the mortgage bubble scam and the expiration of the quantitative easing program, it’s pretty incredible (one might even call it an inspirational testament to the industry's dedication to the cause of high compensation) that bonuses are even in the same ballpark as they used to be.

***

And all of this is just looking at things from a bottom-line, Wall-Street-centric point of view. Looking at the question from the point of view of an ordinary human being, however, Sherman’s thesis is even more nuts. He’s written a sort of investment-banking version of Jimmy Carter’s "malaise" speech, complaining about a lost era of easy money, when in fact there are two damning realities he’s ignored:1. He’s wrong. See the above argument about Europe, QE, etc.

2. Even if he wasn’t wrong, which he is, his reaction to the "news" that Wall Street’s outsized bonuses are dropping is all wrong. If it were true, it would be good news, not bad news.

Since 2008, the rest of America has suffered a severe economic correction. Ordinary people everywhere long ago had to learn to cope with the equivalent of a lower bonus season. When the crash hit, regular people could not make up the difference through bailouts or zero-interest loans from the Fed or leveraged-up synthetic derivative schemes. They just had to deal with the fact that the economy sucked – and they adjusted.

This ought to have been true also on Wall Street, but in a curious development that is somehow not addressed in Sherman's piece, the denizens of the financial services industry managed to maintain their extravagant lifestyle standards in the middle of a historic global economic crash that, incidentally, they themselves caused.

After suffering one truly bad year – 2008, in which the securities industry collectively lost over $42 billion – Wall Street immediately rebounded to post record revenues in 2009, despite the fact that the economy at large did nothing of the sort. The numbers were so huge on Wall Street compared to the rest of the world that Goldman slashed its 4th-quarter bonuses, just so that the final bonus/comp number ($16.2 billion, down from what would have been $21 billion) didn’t look so garish to the rest of broke America.

What Sherman now argues is that Dodd-Frank has so completely hindered Wall Street’s ability to magically invent profits through borrowing and gambling that, unlike those wonderful days in 2009, its fortunes are now reduced to rising and falling – heaven forbid – along with the rest of the economy. Things are so bad, his interview subjects argue, that one is now more likely to make big money going into an actual business that makes an actual product:

"If you’re a smart Ph.D. from MIT, you’d never go to Wall Street now," says a hedge-fund executive. "You’d go to Silicon Valley. There’s at least a prospect for a huge gain. You’d have the potential to be the next Mark Zuckerberg."Once upon a time, Sherman argues, banking was boring. "In the quaint old days, Wall Street tended to earn its profits rather boringly by loaning money, advising mergers, and supervising bond issues and IPOs," he writes. But then, in the eighties, the business became "turbocharged" when new ways to create leverage were introduced. A sudden surge in credit turned this staid business into the realm of super-compensated superheroes:

Credit was the engine that powered the explosion in bank profits. From junk bonds in the eighties to the emerging-markets crisis in the nineties to the subprime mania of the aughts, Wall Street developed new ways to produce, package, and sell debt to willing investors. The alphabet soup of complex vehicles that defined the 2008 crash – CLO, CDO, CDS – had all been developed to sell more credit.But all of this leverage led to problems, Sherman grudgingly concedes, and those problems led to reforms, and now Wall Street is being threatened with a return to those "quaint" days of loaning money and supervising bond issues and such.

Such a return is being demanded by the 99-percenters, much-loathed by Sherman’s interview subjects and portrayed as a bunch of ignoramuses who don’t understand where their bread is buttered. In New York especially, it’s the regular people, he argues, who benefitted from all that crazy leverage. Why, without ginormous leverage-generated bonuses, New York would be … Philadelphia!

Consciously or not, as a city, New York made a bargain: It would tolerate the one percent’s excessive pay as long as the rising tax base funded the schools, subways, and parks for the 99 percent. "Without Wall Street, New York becomes Philadelphia" is how a friend of mine in finance explains it.Sherman then goes further:

In this view, deleveraging Wall Street means killing the goose.Look, the financial services industry should be boring. It should be quaint. Let’s take the municipal debt business. For ages, it was a simple, dull, low-margin sort of industry, in which banks arranged municipal bond issues and made small but dependable profits as cities and towns financed improvements and construction projects.

That system worked seamlessly for decades, until people like Sherman’s interview subjects suddenly decided to make the business exciting. You know what happens when you make municipal debt exciting? Jefferson County, Alabama happens. Or, on a macro level, Greece happens.

When making a few points on mere bond issues stops being enough, and you have to cook up crazy swap schemes and indices to bet against those schemes, ingenious scams allowing politicians to borrow billions of dollars that they will never in a million years be able to pay back, you might end up getting a few parks, schools, and subways in New York.

But what you get everywhere else is a giant clusterfuck that costs the rest of us years and even more billions of tax dollars to remedy.

This is what the protests are all about – it’s anger that Wall Street has been profiting from an imaginary economy that leaves bankers overpaid, but creates damage everywhere else. Sherman doesn’t get this. He seems to subscribe to the well-worn straw-man position that protesters are simply upset that bankers and financiers make a lot of money. Take for example his view on John Paulson, the hedge fund titan who was involved in Goldman’s infamous Abacus deal:

In October, a thousand protesters stood outside John Paulson’s Upper East Side townhouse and offered the hedge-fund billionaire a mock $5 billion check, the amount he earned from his 2010 investments. Later that day, Paulson released a statement attacking the protesters and their movement …. The truth was, Paulson was furious that the protesters had singled him out. Last year, he lost billions of dollars on bad bets on gold and the banking sector. One of his funds posted a 52 percent loss. "The ironic thing is John lost a lot of money this year," a person close to Paulson told me. "The fact that John got roped into this debate highlights their misunderstanding."Hey, asshole: nobody misunderstands anything about John Paulson. They’re not mad that he made billions the year before, and they’re not happy that he lost money this year. They’re mad that the way he made his money in previous years – which involved putting together a born-to-lose portfolio of toxic mortgage bonds and then using Goldman Sachs to dump them on a pair of European banks, who in turn had no idea that Paulson was betting against them.

At least part of this transaction was illegal (so ruled the SEC, anyway), and all of it looks pretty damned underhanded. And if the benefit to society from this sort of work is the tax money New York City received from the proceeds of this fleecing, well, we’re willing to go without those taxes, thank you very much.

Listening to Wall Street whine about how it is misunderstood is nothing new. It’s been going on for years (often in that same mag). But if Sherman’s piece heralds a new era of Wall Street complaining about how it is not only misunderstood but undercompensated, you’ll have to excuse me while I spend the next month or so vomiting into my shoes.

The financial services industry went from having a 19 percent share of America’s corporate profits decades ago to having a 41 percent share in recent years. That doesn’t mean bankers ever represented anywhere near 41 percent of America’s labor value. It just means they’ve managed to make themselves horrifically overpaid relative to their counterparts in the rest of the economy.

A banker's job is to be a prudent and dependable steward of other peoples’ money – being worthy of our trust in that area is the entire justification for their traditionally high compensation.

Yet these people have failed so spectacularly at that job in the last fifteen years that they’re lucky that God himself didn’t come down to earth at bonus time this year, angrily boot their asses out of those new condos, and command those Zagat-reading girlfriends of theirs to start getting acquainted with the McDonalds value meal lineup. They should be glad they’re still getting anything at all, not whining to New York magazine.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Then I read THIS today, which makes me want to punch Bernanke in his stupid beardy face... yes, Americans are saving their HARD EARNED money from you freakazoids. it's bad enough you throw our tax dollars all over the place, that's still not enough, you must have these awful 'economist' articles written to dupe people into thinking you deserve even more of our money, money you want us to spend on Made In China bullshit. To that you get an all resounding N-O. is that simple enough to understand?

There was a comment after this article I particularly enjoyed:

"Where's the money?" Goldstein asked.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

Fuck off, Elites. I'm not religious, but seriously, go rot in hell at this point. Or give it all up and come clean, if you actually want to rectify yourselves. Yeah... like that would ever happen. As Cher from Clueless would say, "As if."

Other countries, especially Central America, where 'mystery diseases' are plaguing the hardworking field laborers, all of you doing backbreaking, brutal work in awful conditions, not just there, but anywhere/everywhere, because of these asshole elites, please, don't blindly hate the west as a whole. it does NOT represent the overall mentality --- there are those of us who don't want you to suffer in the name of the Corporatocracy.

We must prepare ourselves for uprising. It's coming, just not quite yet. Stay smart, use your noggin... and SAVE THAT MONEY (if you can.) Stop pounding yourself silly with expensive alcohol, cut back for your health, your mind, and your wallet. Collectively, our intelligence and awareness should have the ability to establish a force that is insurmountable.

Saturday, February 11, 2012

a cat named frankenstein

one of my favorite photos I took from my most recent excursion, in which I promise to post on here soon...

another saturday night, and i ain't got nobody, the heating pad's warm and it keeps me sane, how i wish i had an able body, i'm in an average way.

Thursday, February 9, 2012

Monday, February 6, 2012

it's okay, dave...

am in the middle of season three of league of gentlemen, which was unfortunately their last. this stuff is so freaky, disgusting, and hilarious, all wrapped up in one little wonderful place called Royston Vasey!

(Tubbs finding out non-local places!)

"This is a local shop, for LOCAL people!"

Sunday, February 5, 2012

'public relations masterpiece.'

The Illusion of Asymmetric Insight by David McRaney

The Misconception: You celebrate diversity and respect others’ points of view.

The Truth: You are driven to create and form groups and then believe others are wrong just because they are others.

In 1954, in eastern Oklahoma, two tribes of children nearly killed each other.

The neighboring tribes were unaware of each other’s existence. Separately, they lived among nature, played games, constructed shelters, prepared food – they knew peace. Each culture developed its own norms and rules of conduct. Each culture arrived at novel solutions to survival-critical problems. Each culture named the creeks and rocks and dangerous places, and those names were known to all. They helped each other and watched out for the well-being of the tribal members.

Scientists stood by, watchful, scribbling notes and whispering. Much nodding and squinting took place as the tribes granted to anthropology and psychology a wealth of data about how people build and maintain groups, how hierarchies are established and preserved. They wondered, the scientists, what would happen if these two groups were to meet.

These two tribes consisted of 22 boys, ages 11 and 12, whom psychologist Muzafer Sherif brought together at Oklahoma’s Robber’s Cave State Park. He and his team placed the two groups on separate buses and drove them to a Boy Scout Camp inside the park – the sort with cabins and caves and thick wilderness. At the park, the scientists put the boys into separate sides of the camp about a half-mile apart and kept secret the existence and location of the other group. The boys didn’t know each other beforehand, and Sherif believed putting them into a new environment away from their familiar cultures would encourage them to create a new culture from scratch.

He was right, but as those cultures formed and met something sinister presented itself. One of the behaviors which pushed and shoved its way to the top of the boys’ minds is also something you are fending off at this very moment, something which is making your life harder than it ought to be. We’ll get to all that it in a minute. First, let’s get back to one of the most telling and frightening experiments in the history of psychology.

Sherif and his colleagues pretended to be staff members at the camp so they could record, without interfering, the natural human drive to form tribes. Right away, social hierarchies began to emerge in which the boys established leaders and followers and special roles for everyone in between. Norms spontaneously generated. For instance, when one boy hurt his foot but didn’t tell anyone until bedtime, it became expected among the group that Rattlers didn’t complain. From then on members waited until the day’s work was finished to reveal injuries. When a boy cried, the others ignored him until he got over it. Regulations and rituals sprouted just as quickly. For instance, the high-status members, the natural leaders, in both groups came up with guidelines for saying grace during meals and correct rotations for the ritual. Within a few days their initially arbitrary suggestions became the way things were done, and no one had to be prompted or reprimanded. They made up games and settled on rules of play. They embarked on projects to clean up certain areas and established chains of command. Slackers were punished. Over achievers were praised. Flags were created. Signs erected.

Soon, the two groups began to suspect they weren’t alone. They would find evidence of others. They found cups and other signs of civilization in places they didn’t remember visiting. This strengthened their resolve and encouraged the two groups to hold tighter to their new norms, values, rituals and all the other elements of the shared culture. At the end of the first week, the Rattlers discovered the others on the camp’s baseball diamond. From this point forward both groups spent most of their time thinking about how to deal with their new-found adversaries. The group with no name asked about the outsiders. When told the other group called themselves the Rattlers, they elected a baseball captain and asked the camp staff if they could face off in a game with the enemy. They named their baseball team the Eagles after an animal they thought ate snakes.

Sherif and his colleagues had already planned on pitting the groups against each other in competitive sports. They weren’t just researching how groups formed but also how they acted when in competition for resources. The fact the boys were already becoming incensed over the baseball field seemed to fall right in line with their research. So, the scientists proceeded with stage two. The two tribes were overjoyed to learn they would not only play baseball, but compete in tug-of-war, touch football, treasure hunts and other summer-camp-themed rivalry. The scientists revealed a finite number of prizes. Winners would receive one of a handful of medals or knives. When the boys won the knives, some would kiss them before rushing to hide the weapons from the other group.

Sherif noted the two groups spent a lot of time talking about how dumb and uncouth the other side was. They called them names, lots of names, and they seemed to be preoccupied every night with defining the essence of their enemies. Sherif was fascinated by this display. The two groups needed the other side to be inferior once the competition for limited resources became a factor, so they began defining them as such. It strengthened their identity to assume the identity of the enemy was a far cry from their own. Everything they learned about the other side became an example of how not to be, and if they did happen to see similarities they tended to be ignored.

The researchers collected data and discussed findings while planning the next series of activities, but the boys made other plans. The experiment was about to spiral out of control, and it started with the Eagles.

Some of the Eagles boys discovered the Rattlers’ flag standing unguarded on the baseball field. They discussed what to do and decided it should be ripped from the ground. Once they had it, a possession of the enemy, a symbol of their tribe, they decided to burn it. They then put its scorched remains back in place and sang Taps. Later, the Rattlers saw the atrocity and organized a raid in which they stole the Eagles’ flag and burned it as payback. When the Eagles discovered the revenge burning, the leader issued a challenge – a face off. The two leaders then met with their followers watching and prepared to fight, but the scientists intervened. That night, the Rattlers dressed in war paint and raided the Eagles’ cabins, turning over beds and tearing apart mosquito netting. The staff again intervened when the two groups started circling and gathering rocks. The next day, the Rattlers painted one of the Eagle boy’s stolen blue jeans with insults and paraded it in front of the enemy’s camp like a flag. The Eagles waited until the Rattlers were eating and conducted a retaliatory raid and then ran back to their cabin to set up defenses. They filled socks with rocks and waited. The camp staff, once again, intervened and convinced the Rattlers not to counterattack. The raids continued, and the interventions too, and eventually the Rattlers stole the Eagles knives and medals. The Eagles, determined to retrieve them, formed an organized war party with assigned roles and planned tactical maneuvers. The two groups finally fought in open combat. The scientists broke up the fights. Fearing the two tribes might murder someone, they moved the groups’ camps away from each other.

You probably suspected this was where the story was headed. You know it is possible in the right conditions that people, even children, might revert to savages. You know about the instant-coffee-version of cultures too. You remember high school. You’ve worked in a cubicle farm. You’ve watched Stephen King movies. People in new situations instinctively form groups. Those groups develop their own language quirks, in-jokes, norms, values and so on. You’ve probably suspected zombies, or bombs, or economic collapse would lead to a battle over who runs Bartertown. In this study, all they had to do was introduce competition for resources and summer camp became Lord of the Flies.

What you may not have noticed though is how much of this behavior is gurgling right below the surface of your consciousness day-to-day. You aren’t sharpening spears, but at some level you are contemplating your place in society, contemplating your allegiances and your opponents. You see yourself as part of some groups and not others, and like those boys you spend a lot of time defining outsiders. The way you see others is deeply affected by something psychologists call the illusion of asymmetric insight, but to understand it let’s first consider how groups, like people, have identities – and like people, those identities aren’t exactly real.

Hopefully by now you’ve had one of those late-night conversations fueled by exhaustion, elation, fear or drugs in which you and your friends finally admit you are all bullshitting each other. If you haven’t, go watch The Breakfast Club and come back. The idea is this: You put on a mask and uniform before leaving for work. You put on another set for school. You have costume for friends of different persuasions and one just for family. Who you are alone is not who you are with a lover or a friend. You quick-change like Superman in a phone booth when you bump into old friends from high school at the grocery store, or the ex in line for the movie. When you part, you quick-change back and tell the person you are with why you appeared so strange for a moment. They understand, after all, they are also in disguise. It’s not a new or novel concept, the idea of multiple identities for multiple occasions, but it’s also not something you talk about often. The idea is old enough that the word person derives from persona – a Latin word for the masks Greek actors sometimes wore so people in the back rows of a performance could see who was on stage. This concept – actors and performance, persona and masks – has been intertwined and adopted throughout history. Shakespeare said, “all the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.” William James said a person “has as many social selves as there are individuals who recognize him.” Carl Jung was particularly fond of the concept of the persona saying it was “that which in reality one is not, but which oneself as well as others think one is.” It’s an old idea, but you and everyone else seems to stumble onto it anew in adolescence, forget about it for a while, and suddenly remember again from time to time when you feel like an impostor or a fraud. It’s ok, that’s a natural feeling, and if you don’t step back occasionally and feel funky about how you are wearing a socially constructed mask and uniform you are probably a psychopath.

Social media confounds the issue. You are a public relations masterpiece. Not only are you free to create alternate selves for forums, websites and digital watering holes, but from one social media service to the next you control the output of your persona. The clever tweets, the photos of your delectable triumphs with the oven and mixing bowl, the funny meme you send out into the firmament that you check back on for comments, the new thing you own, the new place you visited – they tell a story of who you want to be, who you ought to be. They satisfy something. Is anyone clicking on all these links? Is anyone smirking at this video? Are my responses being scoured for grammatical infractions? You ask these questions and others, even if they don’t rise to the surface.

The recent fuss over the over-sharing, over the loss of privacy is just noisy ignorance. You know, as a citizen of the Internet, you obfuscate the truth of your character. You hide your fears and transgressions and vulnerable yearnings for meaning, for purpose, for connection. In a world where you can control everything presented to an audience both domestic or imaginary, what is laid bare depends on who you believe is on the other side of the screen. You fret over your father or your aunt asking to be your Facebook friend. What will they think of that version of you? In flesh or photons, it seems built-in, this desire to conceal some aspects of yourself in one group while exposing them in others. You can be vulnerable in many different ways but not all at once it seems.

So, you don social masks just like every human going back to the first campfires. You seem rather confident in them, in their ability to communicate and conceal that which you want on display and that which you wish was not. Groups too don these masks. Political parties establish platforms, companies give employees handbooks, countries write out constitutions, tree houses post club rules. Every human gathering and institution from the Gay Pride Parade to the KKK works to remain connected by developing a set a norms and values which signals to members when they are dealing with members of the in-group and help identify others as part of the out-group. The peculiar thing though is that once you feel this, once you feel included in a human institution or ideology, you can’t help but see outsiders through a warped lens called the illusion of asymmetric insight.

How well do you know your friends? Pick one out of the bunch, someone you interact with often. Do you see the little ways they lie to themselves and others? Do you secretly know what is holding them back, but also recognize the beautiful talents they don’t appreciate? Do you know what they want, what they are likely to do in most situations, what they will argue about and what they let slide? Do you notice when they are posturing and when they are vulnerable? Do you know the perfect gift? Do you wish they had never went out with so-and-so? Do you sometimes say with confidence, “You should have been there. You would have loved it,” about things you enjoyed for them, by proxy? Research shows you probably feel all these things and more. You see your friends, your family, your coworkers and peers as semipermeable beings. You label them with ease. You see them as the artist, the grouch, the slacker and the overachiever. “They did what? Oh, that’s no surprise.” You know who will watch the meteor shower with you and who will pass. You know who to ask about spark plugs and who to ask about planting a vegetable garden. You can, you believe, put yourself in their shoes and predict their behavior in just about any situation. You believe every person not you is an open book. Of course, the research shows they believe the same thing about you.

In 2001, Emily Pronin and Lee Ross at Stanford along with Justin Kruger at the University of Illinois and Kenneth Savitsky at Williams College conducted a series of experiments exploring why you see people this way.

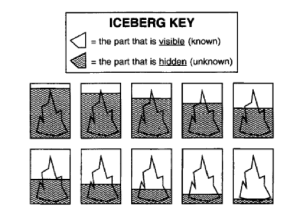

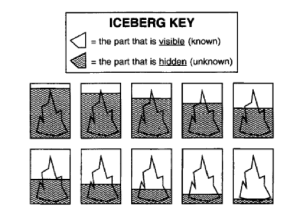

In the first experiment they had people fill out a questionnaire asking them to think of a best friend and rate how well they believed they knew him or her. They showed the subjects a series of photos showing an iceberg submerged in varying levels of water and asked them to circle the one which corresponded to how much of the “essential nature” they felt they could see of their friends. How much, they asked, of your friend’s true self is visible and much is hidden below the surface? They then had the subjects take a second questionnaire which turned the questions around asking them to put themselves in the minds of their friends. How much of their own iceberg did they think their friends could see? Most people rated their insight into their best friend as keen. They saw more of the iceberg floating above the water line. In the other direction they felt the insight their friend’s possessed of them was lacking, most of their own self was submerged.

This and many other studies show you believe you see more of other people’s icebergs than they see of yours; meanwhile, they think the same thing about you.

The same researchers asked people to describe a time when they feel most like themselves. Most subjects, 78 percent, described something internal and unobservable like the feeling of seeing their child excel or the rush of applause after playing for an audience. When asked to describe when they believed friends or relatives were most illustrative of their personalities, they described internal feelings only 28 percent of the time. Instead, they tended to describe actions. Tom is most like Tom when he is telling a dirty joke. Jill is most like Jill when she is rock climbing. You can’t see internal states of others, so you generally don’t use those states to describe their personalities.

When they had subjects complete words with some letters missing (like g–l which could be goal, girl, gall, gill, etc.) and then ask how much the subjects believed those word completion tasks revealed about their true selves, most people said they revealed nothing at all. When the same people looked at other people’s word completions they said things like, “I get the feeling that whoever did this is pretty vain, but basically a nice guy.” They looked at the words and said the people who filled them in were nature lovers, or on their periods, or were positive thinkers or needed more sleep. When the words were their own, they meant nothing. When they were others’, they pulled back a curtain.

When Pronin, Ross, Kruger and Savitsky moved from individuals to groups, they found an even more troubling version of the illusion of asymmetric insight. They had subjects identify themselves as either liberals or conservatives and in a separate run of the experiment as either pro-abortion and anti-abortion. The groups filled out questionnaires about their own beliefs and how they interpreted the beliefs of their opposition. They then rated how much insight their opponents possessed. The results showed liberals believed they knew more about conservatives than conservatives knew about liberals. The conservatives believed they knew more about liberals than liberals knew about conservatives. Both groups thought they knew more about their opponents than their opponents knew about themselves. The same was true of the pro-abortion rights and anti-abortion groups.

The illusion of asymmetric insight makes it seem as though you know everyone else far better than they know you, and not only that, but you know them better than they know themselves. You believe the same thing about groups of which you are a member. As a whole, your group understands outsiders better than outsiders understand your group, and you understand the group better than its members know the group to which they belong.

The researchers explained this is how one eventually arrives at the illusion of naive realism, or believing your thoughts and perceptions are true, accurate and correct, therefore if someone sees things differently than you or disagrees with you in some way it is the result of a bias or an influence or a shortcoming. You feel like the other person must have been tainted in some way, otherwise they would see the world the way you do – the right way. The illusion of asymmetrical insight clouds your ability to see the people you disagree with as nuanced and complex. You tend to see your self and the groups you belong to in shades of gray, but others and their groups as solid and defined primary colors lacking nuance or complexity.

In a political debate you feel like the other side just doesn’t get your point of view, and if they could only see things with your clarity, they would understand and fall naturally in line with what you believe. They must not understand, because if they did they wouldn’t think the things they think. By contrast, you believe you totally get their point of view and you reject it. You see it in all its detail and understand it for what it is – stupid. You don’t need to hear them elaborate. So, each side believes they understand the other side better than the other side understands both their opponents and themselves.

The research suggests you and rest of humanity will continue to churn into groups, banding and disbanding, and the beautiful collective species-wide macromonoculture imagined by the most Utopian of dreams might just be impossible unless alien warships lay siege to our cities. In Sherif’s study, he was able to somewhat reintegrate the boys of the Robber’s Cave experiment by telling them the water supply had been sabotaged by vandals. The two groups were able to come together and repair it as one. Later he staged a problem with one of the camp trucks and was able to get the boys to work together to pull it with a rope until it started. They never fully joined into one group, but the hostilities eased enough for both groups to ride the same bus together back home. It seems peace is possible when we face shared problems, but for now we need to be in our tribes. It just feels right.

So, you pick a team, and like the boys at Robber’s Cave, you spend a lot of time a lot of time talking about how dumb and uncouth the other side is. You too can become preoccupied with defining the essence of your enemies. You too need the other side to be inferior, so you define them as such. You start to believe your persona is actually your identity, and the identity of your enemy is actually their persona. You see yourself in a game of self-deluded poker and assume you are impossible to read while everyone else has obvious tells.

The truth is, you are succumbing to the illusion of asymmetric insight, and as part of a flatter, more-connected, always-on world, you will be tasked with seeing through this illusion more and more often as you are presented with more opportunities than ever to confront and define those who you feel are not in your tribe. Your ancestors rarely made any contact with people of opposing views with anything other than the end of a weapon, so your natural instinct is to assume anyone not in your group is wrong just because they are not in your group. Remember, you are not so smart, and what seems like an insight is often an illusion.

The Misconception: You celebrate diversity and respect others’ points of view.

The Truth: You are driven to create and form groups and then believe others are wrong just because they are others.

In 1954, in eastern Oklahoma, two tribes of children nearly killed each other.

The neighboring tribes were unaware of each other’s existence. Separately, they lived among nature, played games, constructed shelters, prepared food – they knew peace. Each culture developed its own norms and rules of conduct. Each culture arrived at novel solutions to survival-critical problems. Each culture named the creeks and rocks and dangerous places, and those names were known to all. They helped each other and watched out for the well-being of the tribal members.

Scientists stood by, watchful, scribbling notes and whispering. Much nodding and squinting took place as the tribes granted to anthropology and psychology a wealth of data about how people build and maintain groups, how hierarchies are established and preserved. They wondered, the scientists, what would happen if these two groups were to meet.

These two tribes consisted of 22 boys, ages 11 and 12, whom psychologist Muzafer Sherif brought together at Oklahoma’s Robber’s Cave State Park. He and his team placed the two groups on separate buses and drove them to a Boy Scout Camp inside the park – the sort with cabins and caves and thick wilderness. At the park, the scientists put the boys into separate sides of the camp about a half-mile apart and kept secret the existence and location of the other group. The boys didn’t know each other beforehand, and Sherif believed putting them into a new environment away from their familiar cultures would encourage them to create a new culture from scratch.

He was right, but as those cultures formed and met something sinister presented itself. One of the behaviors which pushed and shoved its way to the top of the boys’ minds is also something you are fending off at this very moment, something which is making your life harder than it ought to be. We’ll get to all that it in a minute. First, let’s get back to one of the most telling and frightening experiments in the history of psychology.

Sherif and his colleagues pretended to be staff members at the camp so they could record, without interfering, the natural human drive to form tribes. Right away, social hierarchies began to emerge in which the boys established leaders and followers and special roles for everyone in between. Norms spontaneously generated. For instance, when one boy hurt his foot but didn’t tell anyone until bedtime, it became expected among the group that Rattlers didn’t complain. From then on members waited until the day’s work was finished to reveal injuries. When a boy cried, the others ignored him until he got over it. Regulations and rituals sprouted just as quickly. For instance, the high-status members, the natural leaders, in both groups came up with guidelines for saying grace during meals and correct rotations for the ritual. Within a few days their initially arbitrary suggestions became the way things were done, and no one had to be prompted or reprimanded. They made up games and settled on rules of play. They embarked on projects to clean up certain areas and established chains of command. Slackers were punished. Over achievers were praised. Flags were created. Signs erected.

Soon, the two groups began to suspect they weren’t alone. They would find evidence of others. They found cups and other signs of civilization in places they didn’t remember visiting. This strengthened their resolve and encouraged the two groups to hold tighter to their new norms, values, rituals and all the other elements of the shared culture. At the end of the first week, the Rattlers discovered the others on the camp’s baseball diamond. From this point forward both groups spent most of their time thinking about how to deal with their new-found adversaries. The group with no name asked about the outsiders. When told the other group called themselves the Rattlers, they elected a baseball captain and asked the camp staff if they could face off in a game with the enemy. They named their baseball team the Eagles after an animal they thought ate snakes.

Sherif and his colleagues had already planned on pitting the groups against each other in competitive sports. They weren’t just researching how groups formed but also how they acted when in competition for resources. The fact the boys were already becoming incensed over the baseball field seemed to fall right in line with their research. So, the scientists proceeded with stage two. The two tribes were overjoyed to learn they would not only play baseball, but compete in tug-of-war, touch football, treasure hunts and other summer-camp-themed rivalry. The scientists revealed a finite number of prizes. Winners would receive one of a handful of medals or knives. When the boys won the knives, some would kiss them before rushing to hide the weapons from the other group.

Sherif noted the two groups spent a lot of time talking about how dumb and uncouth the other side was. They called them names, lots of names, and they seemed to be preoccupied every night with defining the essence of their enemies. Sherif was fascinated by this display. The two groups needed the other side to be inferior once the competition for limited resources became a factor, so they began defining them as such. It strengthened their identity to assume the identity of the enemy was a far cry from their own. Everything they learned about the other side became an example of how not to be, and if they did happen to see similarities they tended to be ignored.

The researchers collected data and discussed findings while planning the next series of activities, but the boys made other plans. The experiment was about to spiral out of control, and it started with the Eagles.

Some of the Eagles boys discovered the Rattlers’ flag standing unguarded on the baseball field. They discussed what to do and decided it should be ripped from the ground. Once they had it, a possession of the enemy, a symbol of their tribe, they decided to burn it. They then put its scorched remains back in place and sang Taps. Later, the Rattlers saw the atrocity and organized a raid in which they stole the Eagles’ flag and burned it as payback. When the Eagles discovered the revenge burning, the leader issued a challenge – a face off. The two leaders then met with their followers watching and prepared to fight, but the scientists intervened. That night, the Rattlers dressed in war paint and raided the Eagles’ cabins, turning over beds and tearing apart mosquito netting. The staff again intervened when the two groups started circling and gathering rocks. The next day, the Rattlers painted one of the Eagle boy’s stolen blue jeans with insults and paraded it in front of the enemy’s camp like a flag. The Eagles waited until the Rattlers were eating and conducted a retaliatory raid and then ran back to their cabin to set up defenses. They filled socks with rocks and waited. The camp staff, once again, intervened and convinced the Rattlers not to counterattack. The raids continued, and the interventions too, and eventually the Rattlers stole the Eagles knives and medals. The Eagles, determined to retrieve them, formed an organized war party with assigned roles and planned tactical maneuvers. The two groups finally fought in open combat. The scientists broke up the fights. Fearing the two tribes might murder someone, they moved the groups’ camps away from each other.

You probably suspected this was where the story was headed. You know it is possible in the right conditions that people, even children, might revert to savages. You know about the instant-coffee-version of cultures too. You remember high school. You’ve worked in a cubicle farm. You’ve watched Stephen King movies. People in new situations instinctively form groups. Those groups develop their own language quirks, in-jokes, norms, values and so on. You’ve probably suspected zombies, or bombs, or economic collapse would lead to a battle over who runs Bartertown. In this study, all they had to do was introduce competition for resources and summer camp became Lord of the Flies.

What you may not have noticed though is how much of this behavior is gurgling right below the surface of your consciousness day-to-day. You aren’t sharpening spears, but at some level you are contemplating your place in society, contemplating your allegiances and your opponents. You see yourself as part of some groups and not others, and like those boys you spend a lot of time defining outsiders. The way you see others is deeply affected by something psychologists call the illusion of asymmetric insight, but to understand it let’s first consider how groups, like people, have identities – and like people, those identities aren’t exactly real.

Hopefully by now you’ve had one of those late-night conversations fueled by exhaustion, elation, fear or drugs in which you and your friends finally admit you are all bullshitting each other. If you haven’t, go watch The Breakfast Club and come back. The idea is this: You put on a mask and uniform before leaving for work. You put on another set for school. You have costume for friends of different persuasions and one just for family. Who you are alone is not who you are with a lover or a friend. You quick-change like Superman in a phone booth when you bump into old friends from high school at the grocery store, or the ex in line for the movie. When you part, you quick-change back and tell the person you are with why you appeared so strange for a moment. They understand, after all, they are also in disguise. It’s not a new or novel concept, the idea of multiple identities for multiple occasions, but it’s also not something you talk about often. The idea is old enough that the word person derives from persona – a Latin word for the masks Greek actors sometimes wore so people in the back rows of a performance could see who was on stage. This concept – actors and performance, persona and masks – has been intertwined and adopted throughout history. Shakespeare said, “all the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.” William James said a person “has as many social selves as there are individuals who recognize him.” Carl Jung was particularly fond of the concept of the persona saying it was “that which in reality one is not, but which oneself as well as others think one is.” It’s an old idea, but you and everyone else seems to stumble onto it anew in adolescence, forget about it for a while, and suddenly remember again from time to time when you feel like an impostor or a fraud. It’s ok, that’s a natural feeling, and if you don’t step back occasionally and feel funky about how you are wearing a socially constructed mask and uniform you are probably a psychopath.

Social media confounds the issue. You are a public relations masterpiece. Not only are you free to create alternate selves for forums, websites and digital watering holes, but from one social media service to the next you control the output of your persona. The clever tweets, the photos of your delectable triumphs with the oven and mixing bowl, the funny meme you send out into the firmament that you check back on for comments, the new thing you own, the new place you visited – they tell a story of who you want to be, who you ought to be. They satisfy something. Is anyone clicking on all these links? Is anyone smirking at this video? Are my responses being scoured for grammatical infractions? You ask these questions and others, even if they don’t rise to the surface.

The recent fuss over the over-sharing, over the loss of privacy is just noisy ignorance. You know, as a citizen of the Internet, you obfuscate the truth of your character. You hide your fears and transgressions and vulnerable yearnings for meaning, for purpose, for connection. In a world where you can control everything presented to an audience both domestic or imaginary, what is laid bare depends on who you believe is on the other side of the screen. You fret over your father or your aunt asking to be your Facebook friend. What will they think of that version of you? In flesh or photons, it seems built-in, this desire to conceal some aspects of yourself in one group while exposing them in others. You can be vulnerable in many different ways but not all at once it seems.

So, you don social masks just like every human going back to the first campfires. You seem rather confident in them, in their ability to communicate and conceal that which you want on display and that which you wish was not. Groups too don these masks. Political parties establish platforms, companies give employees handbooks, countries write out constitutions, tree houses post club rules. Every human gathering and institution from the Gay Pride Parade to the KKK works to remain connected by developing a set a norms and values which signals to members when they are dealing with members of the in-group and help identify others as part of the out-group. The peculiar thing though is that once you feel this, once you feel included in a human institution or ideology, you can’t help but see outsiders through a warped lens called the illusion of asymmetric insight.

How well do you know your friends? Pick one out of the bunch, someone you interact with often. Do you see the little ways they lie to themselves and others? Do you secretly know what is holding them back, but also recognize the beautiful talents they don’t appreciate? Do you know what they want, what they are likely to do in most situations, what they will argue about and what they let slide? Do you notice when they are posturing and when they are vulnerable? Do you know the perfect gift? Do you wish they had never went out with so-and-so? Do you sometimes say with confidence, “You should have been there. You would have loved it,” about things you enjoyed for them, by proxy? Research shows you probably feel all these things and more. You see your friends, your family, your coworkers and peers as semipermeable beings. You label them with ease. You see them as the artist, the grouch, the slacker and the overachiever. “They did what? Oh, that’s no surprise.” You know who will watch the meteor shower with you and who will pass. You know who to ask about spark plugs and who to ask about planting a vegetable garden. You can, you believe, put yourself in their shoes and predict their behavior in just about any situation. You believe every person not you is an open book. Of course, the research shows they believe the same thing about you.

In 2001, Emily Pronin and Lee Ross at Stanford along with Justin Kruger at the University of Illinois and Kenneth Savitsky at Williams College conducted a series of experiments exploring why you see people this way.

In the first experiment they had people fill out a questionnaire asking them to think of a best friend and rate how well they believed they knew him or her. They showed the subjects a series of photos showing an iceberg submerged in varying levels of water and asked them to circle the one which corresponded to how much of the “essential nature” they felt they could see of their friends. How much, they asked, of your friend’s true self is visible and much is hidden below the surface? They then had the subjects take a second questionnaire which turned the questions around asking them to put themselves in the minds of their friends. How much of their own iceberg did they think their friends could see? Most people rated their insight into their best friend as keen. They saw more of the iceberg floating above the water line. In the other direction they felt the insight their friend’s possessed of them was lacking, most of their own self was submerged.

This and many other studies show you believe you see more of other people’s icebergs than they see of yours; meanwhile, they think the same thing about you.

The same researchers asked people to describe a time when they feel most like themselves. Most subjects, 78 percent, described something internal and unobservable like the feeling of seeing their child excel or the rush of applause after playing for an audience. When asked to describe when they believed friends or relatives were most illustrative of their personalities, they described internal feelings only 28 percent of the time. Instead, they tended to describe actions. Tom is most like Tom when he is telling a dirty joke. Jill is most like Jill when she is rock climbing. You can’t see internal states of others, so you generally don’t use those states to describe their personalities.

When they had subjects complete words with some letters missing (like g–l which could be goal, girl, gall, gill, etc.) and then ask how much the subjects believed those word completion tasks revealed about their true selves, most people said they revealed nothing at all. When the same people looked at other people’s word completions they said things like, “I get the feeling that whoever did this is pretty vain, but basically a nice guy.” They looked at the words and said the people who filled them in were nature lovers, or on their periods, or were positive thinkers or needed more sleep. When the words were their own, they meant nothing. When they were others’, they pulled back a curtain.

When Pronin, Ross, Kruger and Savitsky moved from individuals to groups, they found an even more troubling version of the illusion of asymmetric insight. They had subjects identify themselves as either liberals or conservatives and in a separate run of the experiment as either pro-abortion and anti-abortion. The groups filled out questionnaires about their own beliefs and how they interpreted the beliefs of their opposition. They then rated how much insight their opponents possessed. The results showed liberals believed they knew more about conservatives than conservatives knew about liberals. The conservatives believed they knew more about liberals than liberals knew about conservatives. Both groups thought they knew more about their opponents than their opponents knew about themselves. The same was true of the pro-abortion rights and anti-abortion groups.

The illusion of asymmetric insight makes it seem as though you know everyone else far better than they know you, and not only that, but you know them better than they know themselves. You believe the same thing about groups of which you are a member. As a whole, your group understands outsiders better than outsiders understand your group, and you understand the group better than its members know the group to which they belong.

The researchers explained this is how one eventually arrives at the illusion of naive realism, or believing your thoughts and perceptions are true, accurate and correct, therefore if someone sees things differently than you or disagrees with you in some way it is the result of a bias or an influence or a shortcoming. You feel like the other person must have been tainted in some way, otherwise they would see the world the way you do – the right way. The illusion of asymmetrical insight clouds your ability to see the people you disagree with as nuanced and complex. You tend to see your self and the groups you belong to in shades of gray, but others and their groups as solid and defined primary colors lacking nuance or complexity.

“Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself; (I am large, I contain multitudes.)”The two tribes of children in Oklahoma formed because groups are how human beings escaped the Serengeti and built pyramids and invented Laffy Taffy. All primates depend on groups to survive and thrive, and human groups thrive most of all. It is in your nature to form them. Sherif’s experiment with the boys at Robber’s Cave showed how quickly and easily you do so, how your innate drive to develop and observe norms and rituals will express itself even in a cultural vacuum, but there is a dark side to this behavior. As psychologist Jonathan Haidt says, our minds “unite us into teams, divide us against other teams, and blind us to the truth.” It’s that last part that keeps getting you into trouble. Just as you don a self, a persona, and believe it to be thicker and harder to see through than those of your friends, family and peers, you too believe the groups to which you belong are more complex, more diverse and granular than are groups of which you could never imagine yourself a member. When you feel the warm comfort of belonging to a team, a tribe, a group – to a party, an ideology, a religion or a nation – you instinctively turn others into members of outgroups, into outsiders. Just as soldiers come up with derogatory names for enemies, every culture and sub-culture has a collection of terms for outsiders so as to better see them as a single-minded collective. You are prone to forming and joining groups and then believing your groups are more diverse than outside groups.

-Walt Whitman from Song of Myself, Leaves of Grass

In a political debate you feel like the other side just doesn’t get your point of view, and if they could only see things with your clarity, they would understand and fall naturally in line with what you believe. They must not understand, because if they did they wouldn’t think the things they think. By contrast, you believe you totally get their point of view and you reject it. You see it in all its detail and understand it for what it is – stupid. You don’t need to hear them elaborate. So, each side believes they understand the other side better than the other side understands both their opponents and themselves.

The research suggests you and rest of humanity will continue to churn into groups, banding and disbanding, and the beautiful collective species-wide macromonoculture imagined by the most Utopian of dreams might just be impossible unless alien warships lay siege to our cities. In Sherif’s study, he was able to somewhat reintegrate the boys of the Robber’s Cave experiment by telling them the water supply had been sabotaged by vandals. The two groups were able to come together and repair it as one. Later he staged a problem with one of the camp trucks and was able to get the boys to work together to pull it with a rope until it started. They never fully joined into one group, but the hostilities eased enough for both groups to ride the same bus together back home. It seems peace is possible when we face shared problems, but for now we need to be in our tribes. It just feels right.

So, you pick a team, and like the boys at Robber’s Cave, you spend a lot of time a lot of time talking about how dumb and uncouth the other side is. You too can become preoccupied with defining the essence of your enemies. You too need the other side to be inferior, so you define them as such. You start to believe your persona is actually your identity, and the identity of your enemy is actually their persona. You see yourself in a game of self-deluded poker and assume you are impossible to read while everyone else has obvious tells.

The truth is, you are succumbing to the illusion of asymmetric insight, and as part of a flatter, more-connected, always-on world, you will be tasked with seeing through this illusion more and more often as you are presented with more opportunities than ever to confront and define those who you feel are not in your tribe. Your ancestors rarely made any contact with people of opposing views with anything other than the end of a weapon, so your natural instinct is to assume anyone not in your group is wrong just because they are not in your group. Remember, you are not so smart, and what seems like an insight is often an illusion.

peanut poses for peebleboy, life subscription: only 50 quid! (£££)

my new piece.

"look at my awkward hand."

"i don't do photoshoots."

"to retaliate, ima gonnas shoot you instead!"

"incorrect depiction of oneself, let's try this again.."

"HOWS THIS FOR TRIGGER HAPPY?!"

Friday, February 3, 2012

Thursday, February 2, 2012

Wednesday, February 1, 2012

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

What happened to the housing market is what has been happening for decades to the economy in general. Inflate values, promote borrowing to support the inflated values, deflate values and, then, foreclose on the delinquent borrowed loans.

The sad part is that the American economy has been drained of it's capacity to continue the bubble economy. All of the wealth has been foreclosed upon and the only place left to continue the game is in foreign places. That is why investors have taken their capital to foreign lands.

As for America? It can accept austerity and reach it's new normal, as a second world nation. The elites would be just as happy exploiting Brazilian, Russian, Indian or Chinese labor, inflating their economies, bursting their bubbles and moving on to the next weaker nations.

If we were smart, we would realize the game being played and unite the world against the elite forces that perpetuate this game. Sadly, Americans are blind to the game. Blinded by nationalis

Sorry. That ship has sailed. The best we can do is to expel the elites, rebuild America with a sustainabl